Recommender System Attribution with Model Interpretability methods

Introduction

Recommender systems use machine learning models to find items (eg. movies, songs) that a user may like. Data available to recommender systems include past user-item interactions, similarity of user behavior, item features, user’s context, among other available information. We focus on sequential recommender models, which predict future items that a user may interact with based on that user’s interaction history. The performance of recommender systems has significant financial implications.

The goal of our study is to examine why certain recommendations are bad and find methods to improve them. Before this project was put on hold, I adapted model interpretability methods to identify “bad” training data. Once identified, a new model was trained with the “bad” data removed/corrected. Examples of “bad” data include users erroenously clicking on unrelated items and users missing relevant items. Because we assume that all user-item interactions reflect a user’s preference, “bad” data significantly affects the quality of recommendations.

Long Short-Term Memory

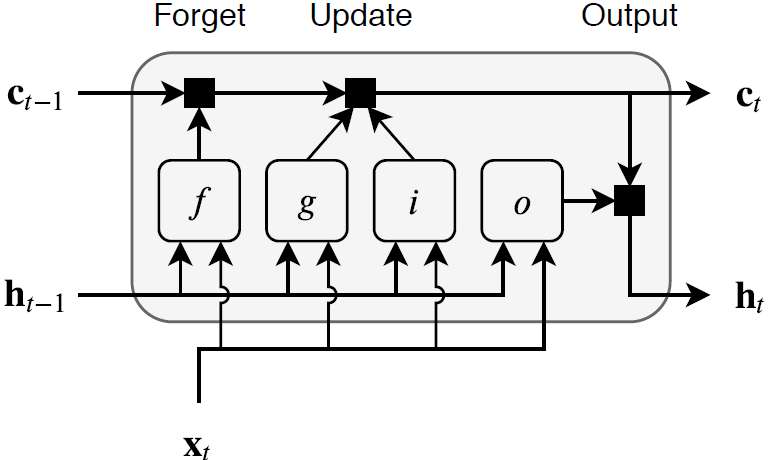

Long Short-Term Memory is a recurrent neural nework composed of a memory cell, input gate, output gate, and forget gate (Hochreiter and Schmidhuber 1997).

The memory cell remembers information over long sequences. The input gate decides how much of a new input should be remembered, the output gate decides how much of the information in the memory cell should influence the output, and the forget gate decides how much information to discard from the memory cell.

Sequential recommendation model

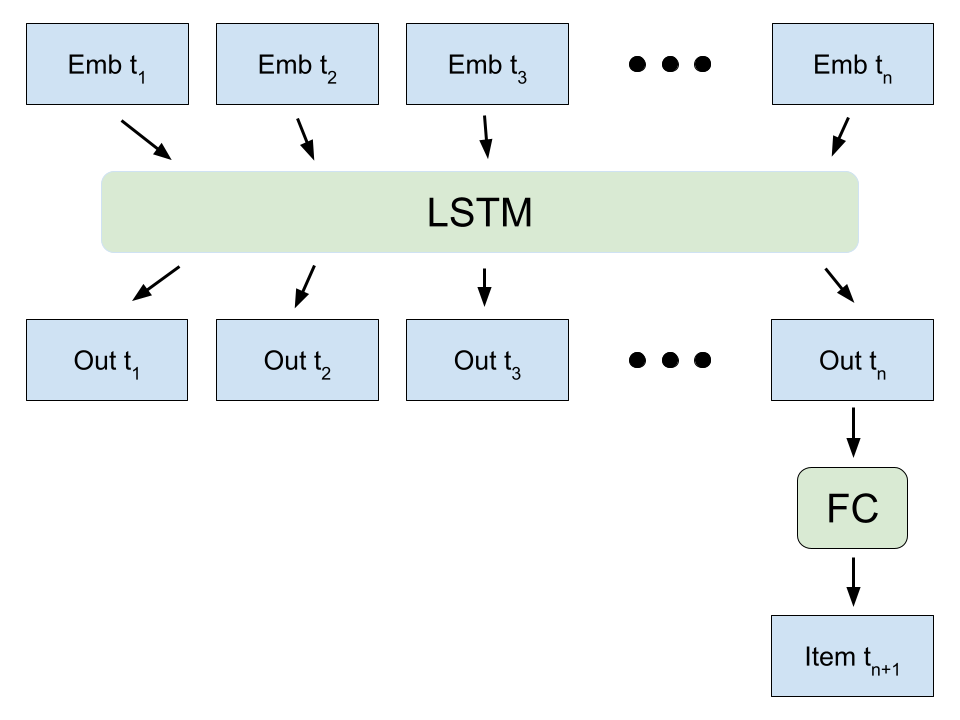

We use a fairly simple sequential recommender system based on a LSTM (Long Short-Term Memory) model.

| Embedding Step | LSTM step |

|---|---|

|

|

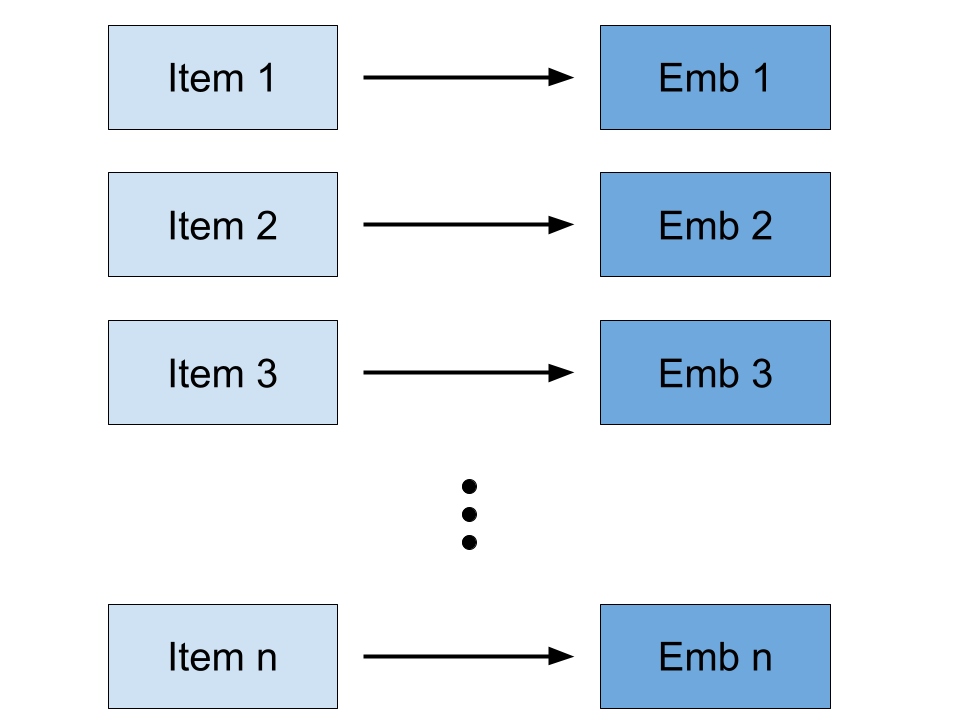

First, each item is mapped to a vector embedding. Next, fixed length sequences of vector embeddings are fed into a LSTM model. The last timestep index of the LSTM’s output is then fed into a fully connected layer to predict the next item a user may interact with.

TracIn

TracIn (Pruthi et al. 2020) was one method we used to identify “bad” training data. Other methods used include integrated gradients.

TracIn computes the influence of a training instance on a prediction made by the model. The method estimates the change in test loss when the training instance of interest is used to update model weights. The idealized notion of influence of a training instance on a prediction is defined as the total reduction in loss on test data \(z'\) whenever training data \(z\) is used. Training data that reduce loss are “proponents” and training data that increase loss are “opponents.” Using TracIn, “bad” data is equivalent to “opponents.”

\[ TracInIdeal(z, z') = \sum_{t: z_t = z} \ell(w_t, z') - \ell(w_{t+1}, z') \]

The authors provide a practical implementation, using saved checkpoints.

\[ TracInCP(z, z') = \sum_{i = 1}^k \eta \nabla \ell(w_{t_i}, z) \cdot \nabla \ell(w_{t_i}, z') \]

This formula is derived using a first order approximation \[ \ell(w_{t+1}, z') = \ell(w_t, z') + \nabla \ell(w_t, z') \cdot (w_{t+1} - w_t) + O(||w_{t+1} - w_t||^2) \]

and change in parameter formula

\[ w_{t+1} - w_t = -\eta \nabla \ell(w_t, z_t) \]

Data

We use the Movielens 1M Dataset for experiments (Maxwell 2015). The dataset contains 1 million ratings from 6000 users on 4000 movies with timestamps for each rating. For results shown below, we use a subset of the dataset: around 100000 training sequences.

TracIn applied to Movielens

Code for our implementation of TracIn and LSTM training can be found here.

We apply TracIn to Movielens and find proponents/opponents for several well-known movies.

| Test item | Top 2 proponents | Top 2 opponents |

|---|---|---|

| Return of the Jedi (1983) | Star Wars (1977), Toy Story (1995) | Pretty Woman (1990), Mrs. Doubtfire (1993) |

| Star Trek III: The Search for Spock (1984) | Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country (1991), Speed (1994) | Sense and Sensibility (1995), Amadeus (1984) |

| L.A. Confidential (1997) | English Patient, The (1996), Contact (1997) | Twister (1996), Die Hard 2 (1990) |

| Citizen Kane (1941) | Amadeus (1984), Casablanca (1942) | Batman Returns (1992), Batman Forever (1995) |

| Top Gun (1986) | Jurassic Park (1993), Speed (1994) | English Patient, The (1996), Sense and Sensibility (1995) |

| Jaws (1975) | Alien (1979), Schindler’s List (1993) | Liar Liar (1997), Boogie Nights (1997) |

| G.I. Jane (1997) | Air Force One (1997), Contact (1997) | Fargo (1996), Return of the Jedi (1983) |

From a quick glimpse, these results seem to make sense: eg. “Star Wars” positively influencing predictions for “Return of the Jedi.”

Training new model with opponents removed

With opponents identified, we train a new model with 500 opponent training sequences removed and compare results to that of a model trained on the original data.

| Train data | Test MRR (mean reciprocal rank) | Test Recall@10 |

|---|---|---|

| Original | 0.0238 | 0.0452 |

| 500 opponents removd | 0.0264 | 0.0514 |

We see that test performance (test data is kept constant for both settings) improves once opponents are removed.

Future work

I worked on this project during Fall 2022 - Spring 2023. This project was put on hold as my PhD mentor found another project more relevant to his research interests at the time: a project on safety guardrails for Vision-Language models.

If I were to revist this project, I am interested in applying TracIn (or other similar methods) to the medical domain. TracIn could be used to identify “opponent” medical images for computer vision tasks.

Code repository: https://github.com/donghyunkm/recommenderAttribution